Towards Understanding Multi-Task Learning (Generalization) of LLMs via Detecting and Exploring Task-Specific Neurons

Introduction

Instruction Tuning involves fine-tuning a language model on a collection of instruction-formatted multi-task datasets, with the goal of enabling the language model to generalize to unseen tasks. This paper investigates the inner workings of multi-task learning (from the perspective of neurons) in LMs, which still remains an open question. Specifically, the authors investigate the following three research questions:

Research Questions

- Do tasks-specific neurons exist in LMs, from a broad perpspective?

- If they exist, can they facilitate the understanding of the multi-task learning mechanisms in LMs?

- Can we improve LMs by exploring such neurons?

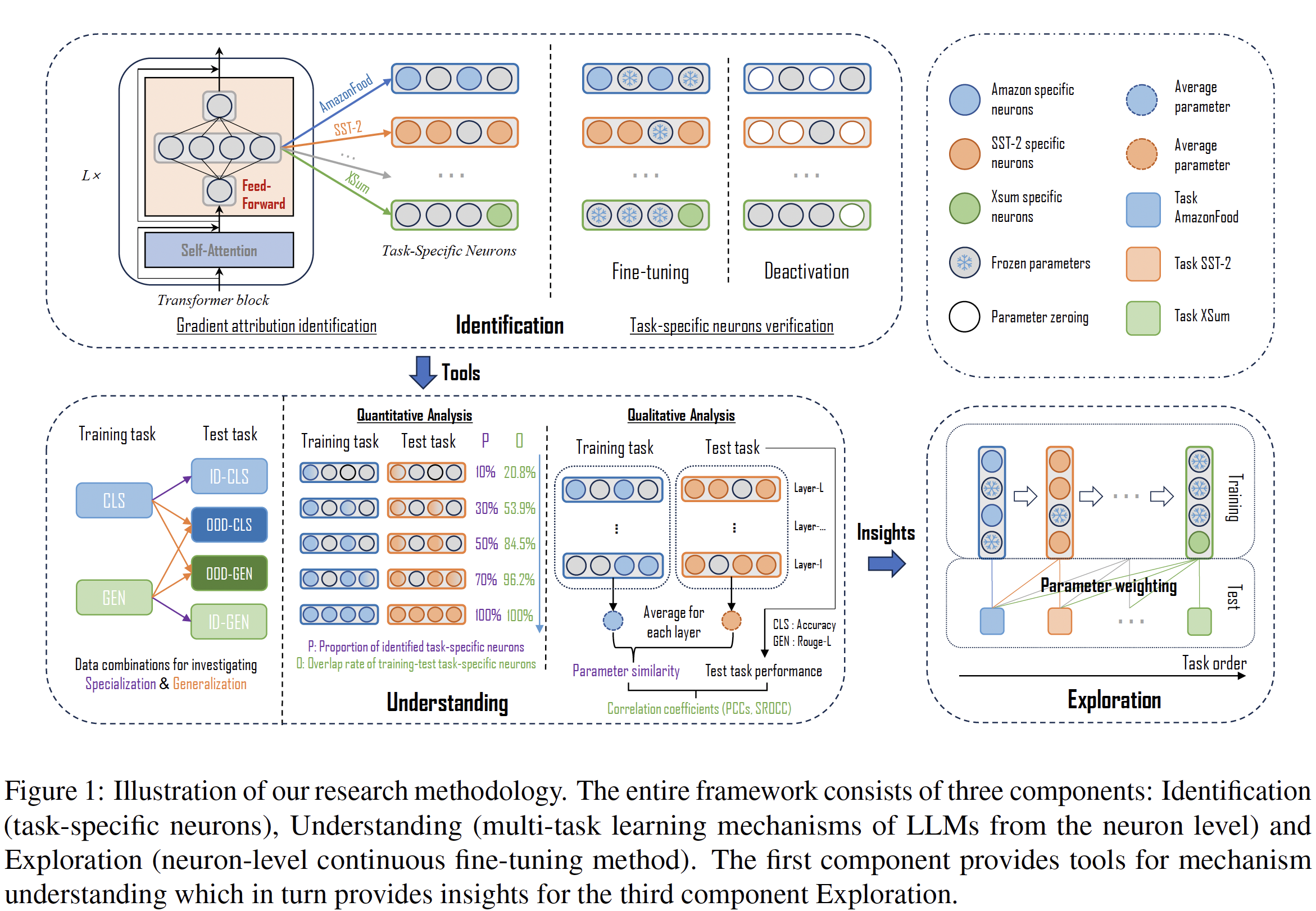

On a very high level, this paper (empirically) detects task-sensitive neurons in LMs via gradient attribution on task-specific data and derives insights into generalization across tasks with the detected task-specific neurons. Further, a Neuron-level Continuous learning Fine-Tuning (NCFT) method is proposed for mitigating catastrophic forgetting.

Methodology

Identifying Task-Specific Neurons

What is a neuron here? An autoregressive transformer-based LM (such as GPT-2) consists of an embedding layer, multiple residual blocks and an unembedding layer. Each residual block consists of a multi-head self-attention (MHA) module and a feed-forward network (FFN). The authors only focus on FFN citing that these have been demonstrated to store a large amount of parametric knowledge.

The FFN module at layer \(i\) can be formulated as

\[\mathbf{h}^i=f(\mathbf{\tilde{h}^i}\mathbf{W}_1^i).\mathbf{W}_2^{i}\]where \(\mathbf{\tilde{h}}^i\in\mathbb{R}^d\) denotes the output of the MHA module at layer \(i\), which is also the input of the current FFN module. \(\mathbf{h}^i\) denotes the output of the current FFN module. \(\mathbf{W}_1^i\in\mathbb{R}^{d\times d_{ff}}\) and \(\mathbf{W}_2^i\in\mathbb{R}^{d_{ff}\times d}\) are the weights of the FFN module at layer \(i\) and \(f(\cdot)\) denotes the activation function. A neuron is defined as a column in \(\mathbf{W}_1^i\) or \(\mathbf{W}_2^i\), which is a linear transformation of the input to the FFN module.

Inspired from importance-based neuron fine-tuning studies and neuronal interpretability, the authors employ gradient-attribution to quantify each neuron’s relevance score for a given task. A relevance score \(\mathcal{R}_j^i\) is first defined of the \(j\)-th neuron in the \(i\)-th layer to a certain task:

\[\mathcal{R}_i^j=\left|\Delta \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{\omega}_j^i)\right|\]where \(\mathbf{\omega}_j^i\) is the output of the \(j\)-th neuron in the \(i\)-th layer, and \(\Delta \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{\omega}_j^i)\) is the change in loss between setting \(\mathbf{\omega}_j^i\) to zero and the original value.

Taylor Expansion can be used to approximate the change in loss when removing a particular neuron. Let \(\mathbf{\omega}^i\) be the output of the \(i\)-th layer and \(\Omega\) represent the set of other neurons. Assuming independence of each neuron in the model, the change of loss when removing the \(j\)-th neuron in layer \(i\) can be represented as:

\[\left| \Delta \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{\omega}_j^i) \right| = \left| \mathcal{L}(\Omega, \mathbf{\omega}_j^i=0) - \mathcal{L}(\Omega, \mathbf{\omega}_j^i) \right|\]where \(\mathcal{L}(\Omega, \mathbf{\omega}_j^i=0)\) is the loss when the \(j\)-th neuron is pruned and \(\mathcal{L}(\Omega, \mathbf{\omega}_j^i)\) is loss if it is not pruned. The first-order Taylor series approximation for the function \(\mathcal{L}(\Omega, \mathbf{\omega}_j^i)\) at \(\mathbf{\omega}_j^i=0\) is:

\[\mathcal{L}(\Omega, \mathbf{\omega}_j^i) \approx \mathcal{L}(\Omega, \mathbf{\omega}_j^i=0) + \frac{\partial\mathcal{L}(\Omega, \mathbf{\omega}_j^i)}{\partial\mathbf{\omega}_j^i} \cdot \mathbf{\omega}_j^i\]Hence, the relevance score can be approximated as:

\[\mathcal{R}_j^i \approx \left| \frac{\partial\mathcal{L}(\Omega, \mathbf{\omega}_j^i)}{\partial\mathbf{\omega}_j^i} \cdot \mathbf{\omega}_j^i \right|\]Neurons with top \(k\%\) relevance scores are considered as task-specific neurons, where \(k\) is a predefined hyperparameter.

Understanding Multi-Task Learning in LMs by analyzing task-specific neurons

For a quantitive study of the impact on cross-task generalization and single-task specialization, the authors fine-tune varying proportions of task-specific neurons. During fine-tuning, only the neurons specific to the current training task are trained. For measuring specialization performance, the test set of the training task (in-domain, ID) is used, while the test set of other tasks (out-of-domain, OOD) is used for measuring generalization performance.

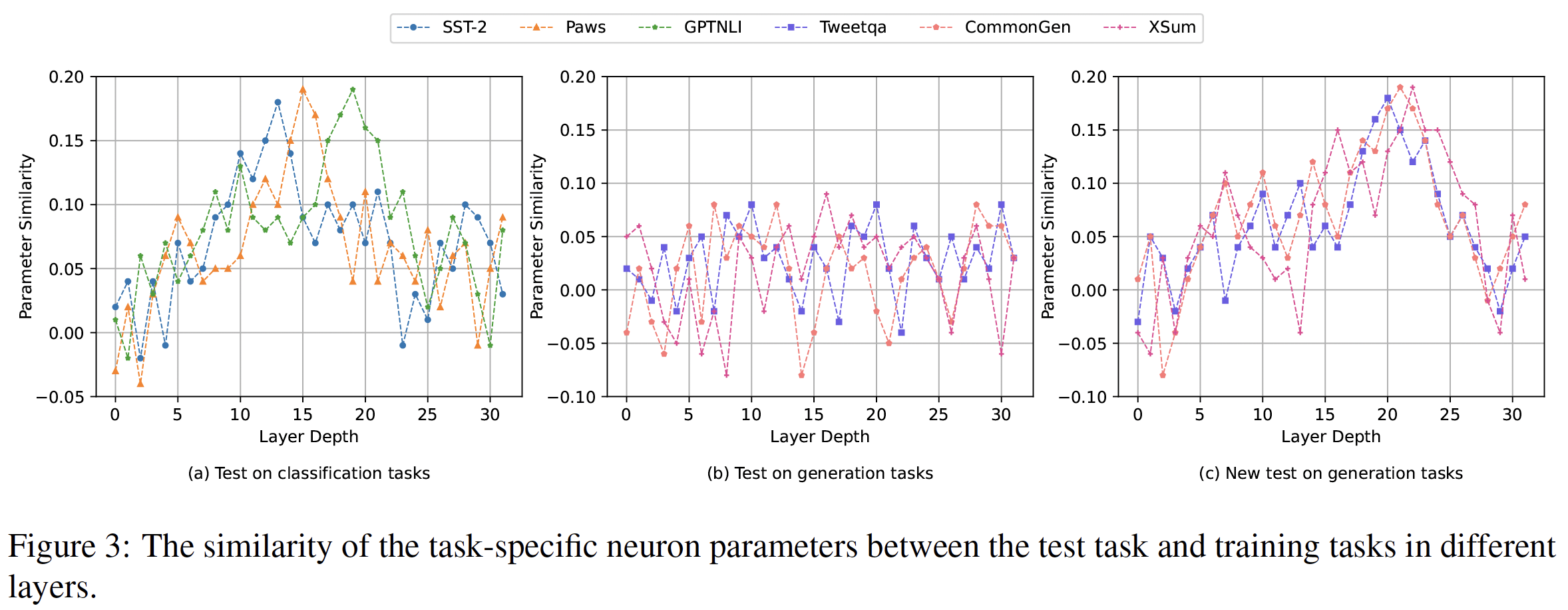

For qualitative analysis, the authors compute the task-specific neuron parameters cosine similarity within a model between the task used to train that model and test task, and study how this similarity varies across different layers of the model, aiming to investigate knowledge transfer between the test task and training task. Also, the authors compute the correlation coefficient between this parameter similarity and performance on corresponding test set, aiming to further demonstrate association between parameter similarity and generalization.

Exploring Task-Specific Neurons to Mitigate Catastrophic Forgetting in LMs

Because of parameter interference between tasks, an LM trained on multiple tasks can effectively handle multiple tasks but does not necessarily achieve optimal performance on a single task. Similarly, catastrophic forgetting can also be caused by parameter interference. The authors propose a Neuron-level Continuous learning Fine-Tuning (NCFT) method to mitigate catastrophic forgetting in continual learning.

Given a sequence of tasks \(D_1, \dots, D_N\), the tasks arrive sequentially in the order of task sequence during the training stage. For current task \(D_n\), the authors update only the neuron-specific parameters of the current task, while keeping the other parameters frozen. During the test stage, the inference is executed as usual.

Experiments and Results

1. Do task-specific neurons exist in LMs, from a broad perpspective?

Experiment-1

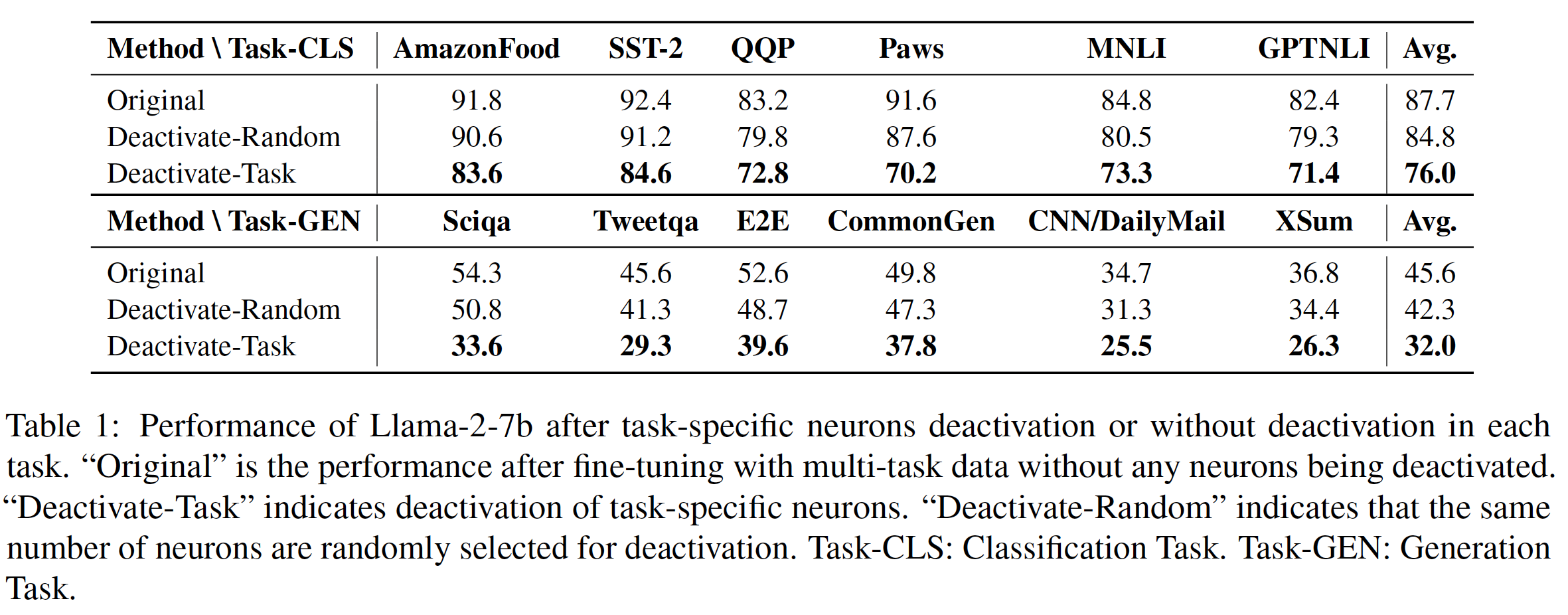

The authors deactivated task-specific neurons to conduct deactivation experiments. Deactivation was achieved by setting the activation value of these neurons to zero or by directly setting the corresponding parameter to zero. \(k\) was set to \(10\) in these experiments.

As can be seen from Table-1, deactivating 10% task-specific neurons has a large negative impact on task-specific processing capacity whereas deactivating same number of randomly selected neurons results in a small impact.

Experiment-2

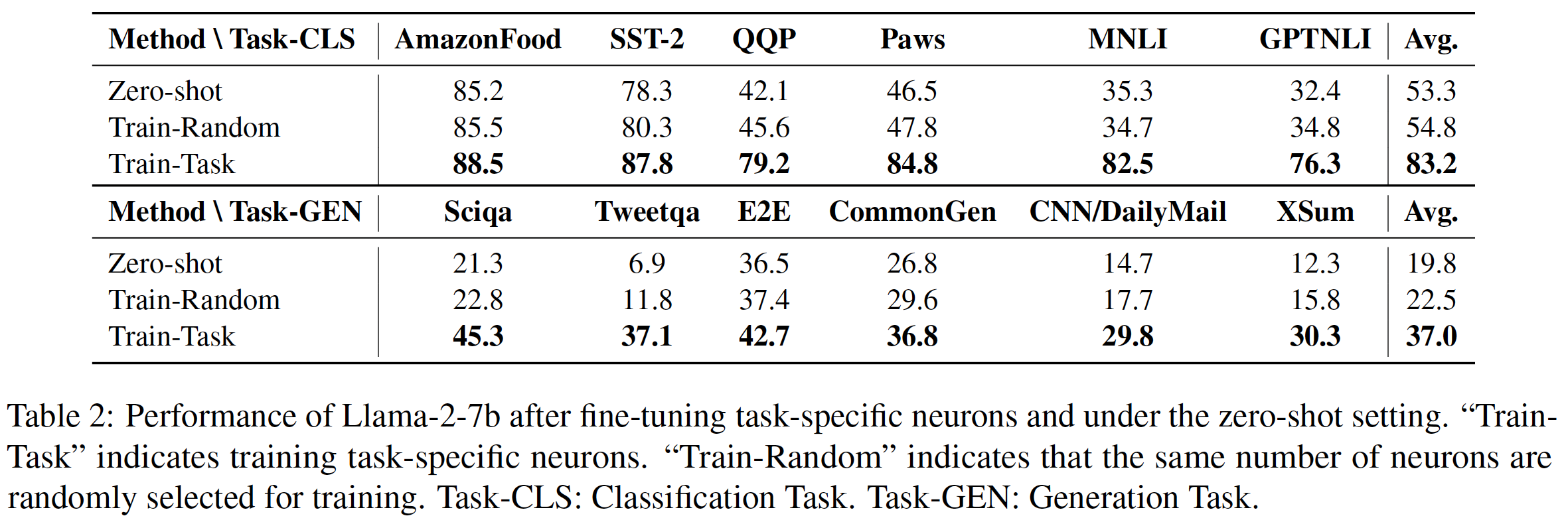

The authors conducted fine-tuning experiments where only task-specific neurons were updated with parameters and other neurons were frozen during training.

As can be seen from Table-2, the fine-tuning approach to task-specific neurons yields remarkable improvements compared to the approach of fine-tuning randomly selected neurons. This is consistent across task categories (except Amazonfood - probably it has a good enough zero-shot performance).

Based on Experiment-1 and Experiment-2, we can empirically assert the presence of task-specific neurons within LMs.

2. If task-specific neurons exist, can they facilitate the understanding of the multi-task learning mechanisms in LMs?

Specialization, Generalization and trade-off

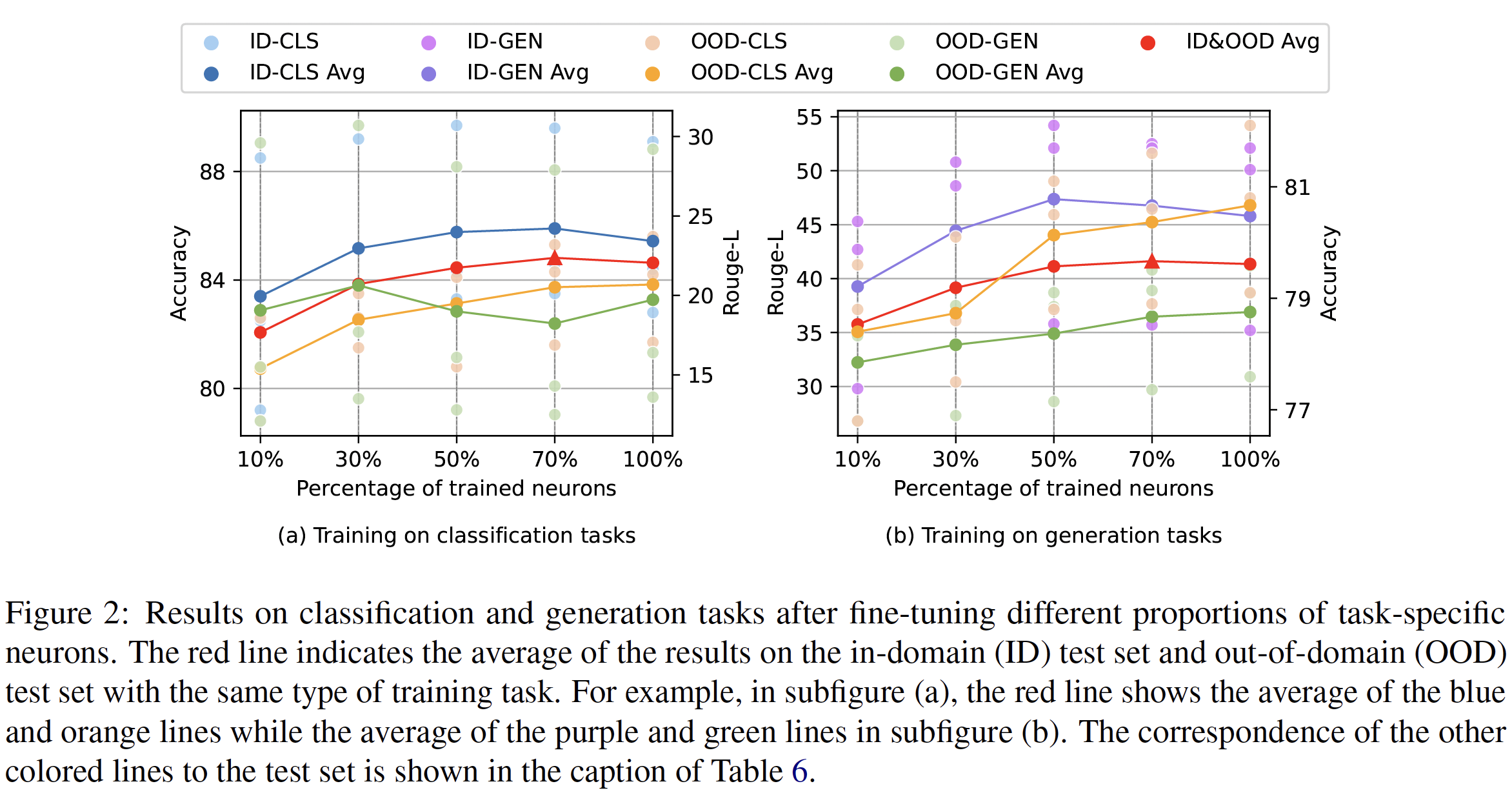

The authors controlled the proportion of fine-tuned task-specific neurons to conduct experiments on the various training-test combinations. Figure-2 shows results for all training-test combinations. In each subfigure, we only focus on the trend for each colored line. Comparisons between different color lines are meaningless because they represent different tasks.

As the proportion of trained task-specific neurons increases, the specialization performance for both classification and generation tasks first ascends and then declines, reaching its peak at 70% for the classification task and at 50% for the generation task. This could be due to parameter interference between different tasks induced by simultaneous training of three tasks. This interference further results in specialization performance of a single task not exhibiting a continuous improvement as more parameters are trained.

The authors also conducted ablation experiments where they trained a model for each task, meaning that finetuning of task-specific neurons was conducted individually. They observed a continous enhancement in performance as the proportion of neurons increases.

As the proportion of trained task-specific neurons increases, the authors find a continuous increasing trend for the perfromance of generalization from the trained classification tasks to other classification tasks. Similar trend is also observed for generation tasks. The authors also look at overlap rate of task-specific neurons between training tasks and test tasks as:

\[overlap(x, y) = \frac{\mathcal{N}_x \cap \mathcal{N}_y}{\mathcal{N}_x \cup \mathcal{N}_y}\]where \(\mathcal{N}_{tasks}\) denotes the set of task-specific neurons. Overall set of task-specific neurons of three training tasks is denoted as \(\mathcal{N}_x\) and the set of task-specific neurons of the test task is denoted as \(\mathcal{N}_y\). The authors found that as proportion of task-specific neurons increases, overlap rate also experiences a significant surge. A plausible explanation for this is that overlap of task-specific neurons contributes to transfer learning between tasks, ultimately resulting in consistently higher generalization performance.

The authors also observed no generalization from classification tasks to generation tasks, which is probably because classification tasks are usually easier as they need to predict a single label.

The authors found that when training all parameters of the model under the multi-task learning setup, inevitable interference among task occurs, thereby diminishing the efficacy of individual tasks to some degree. Furthermore, experiments illustrate the efficacy of controlling the appropriate proportion of fine-tuned task-specific neurons. Additionally there is a significant overlap of task-specific neurons and generalization performance across tasks. However, this overlap does not always guarantee deterministic generalization, as numerous factors also play pivotal roles.

Parameters of Task-Specific Neurons

The authors evaluated similarity of specific neuron parameters for the training and test tasks aiming to conduct a qualitative analysis of generalization provenance. The authors trained a separate model for each of the six training tasks - \(M_1, \dots, M_6\). Then these models are tested on six out-of-domain test tasks - \(T_1, \dots, T_6\). In a particular layer, for model \(M_i\) and test task \(T_j\), \(\mathbf{P}_i^i\) and \(\mathbf{P}_j^i\) are used to denote the task-specific neuron parameters of training task \(i\) and test task \(j\) in \(M_i\) respectively. Cosine similarity between \(\mathbf{P}_i^i\) and \(\mathbf{P}_j^i\) is then computed. For test task \(T_j\), average of 6 similarities is calculated. Figure-3 illustrates the similarity of different layers for three different settings.

The authors findings suggest a correlation between generalization across different tasks and similarity of task-specific neuron parameters. When layers after a certain depth are reached, the model can learn shared knowledge between tasks, which contributes to generalization performance. The conclusions provide a guideline for improving generalization performance across tasks.

3. Can we improve LMs by exploring such neurons?

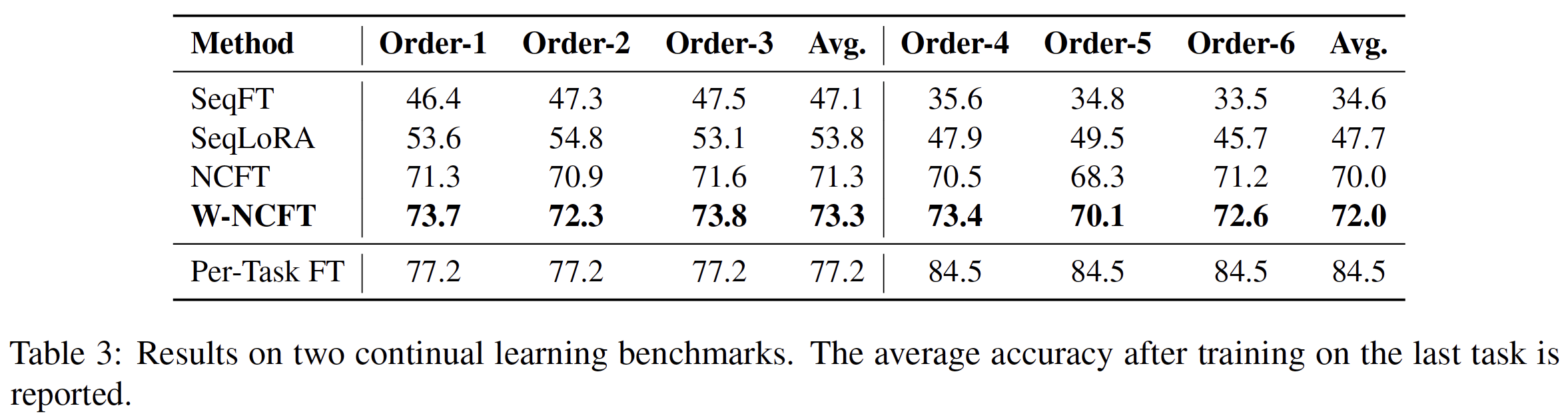

The authors conducted experiments to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed NCFT method. The results are shown in Table-3. The proposed NCFT method significantly outperforms the baseline method, which is consistent with the authors’ hypothesis that the proposed method can mitigate catastrophic forgetting in continual learning.

Summary

- The authors presented a methodology framework for understanding multi-task learning and cross-task generalization of LLMs from the perspective of neurons.

- Using the framework, extensive analysis of LMs is conducted to identify task-specific neurons that are highly correlated with specific tasks.

- Using these task specific neurons, the authors investigated two common problems of LMs in multi-task learning and continuous learning: generalization and catastrophic forgetting.

- Authors found that the identified task-specific neurons is strongly associated with generalization.

- The parameter similarity of these neurons reflects degree of knowledge sharing, contributing to generalization.

- A neuron-level continuous fine-tuning method is proposed for effective mitigation of catastrophic forgetting in continual learning.

References

Leng, Y. and Xiong, D., 2024. Towards understanding multi-task learning (generalization) of llms via detecting and exploring task-specific neurons. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.06488.