🤔 Taken for Granted? It's time we reconsider the Instruction Tuning Loss! 👉

Uncovering the benefits of Weighted Instruction Tuning (WIT)

TL;DR — Small Tweaks, Big Gains 🤷

Instruction Tuning is the cornerstone of language model (LM) post-training — it is what enables the models to “follow” user instructions instead of merely completing text. Yet surprisingly, one critical piece has largely flown under the radar: the Loss Function!

In our recent work, On the Effect of Instruction Tuning Loss on Generalization(co-authored with Anwoy Chatterjee, Sumit Bhatia and Tanmoy Chakraborty), soon to appear in the Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics (TACL), we revisit this overlooked choice and introduce Weighted Instruction Tuning (WIT) — a simple yet effective alternative that lets you assign different weights to prompt and response tokens during training.

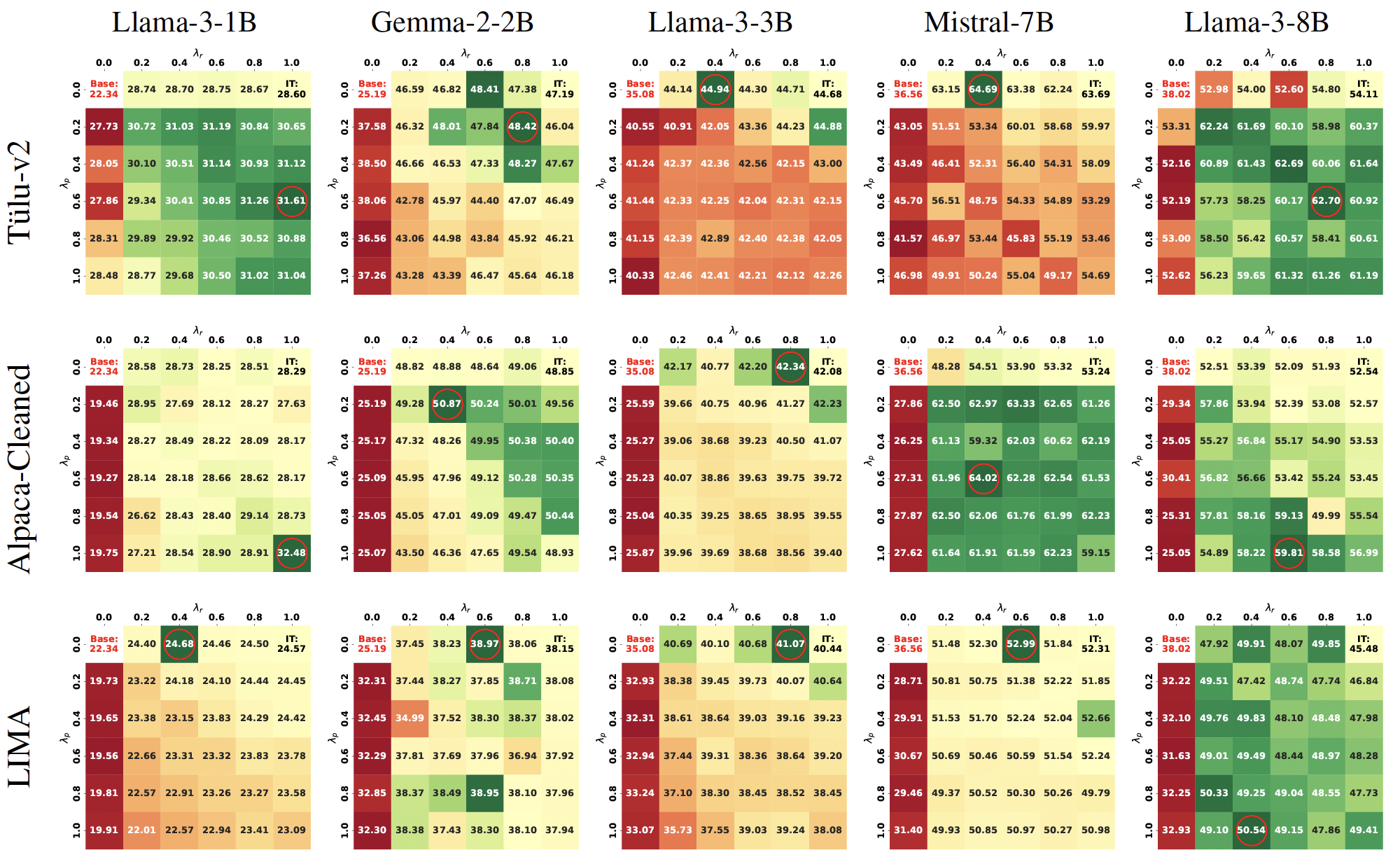

We found that assigning a low-to-moderate (0-0.5) weight to the prompt tokens and a moderate-to-high (0.5-1) weight to the response tokens consistently yields best-performing models across settings — when tested extensively across five models (spanning sizes and families), three instruction tuning datasets (varying sizes), and five diverse benchmarks…

WIT-finetuned models not only demonstrate consistent improvement in generalization (average relative gain of 6.55%), but also are more robust to minor changes in prompts as well as serve as a stronger bases for subsequent preference alignment tuning!

Introduction — The Ubiquitous Loss Function We’ve Barely Scrutinized

Instruction Tuning has emerged as an important step in the post-training phase of LMs. It is what makes today’s language models capable of “following” user instructions — from summarizing a news article to giving life advice in the tone of a pirate!

Behind the scenes, instruction tuning works by finetuning a pretrained LM on a collection of (prompt, response) pairs comprising of a diverse set of tasks — where prompts encode tasks in the form of natural language instructions and responses provide ideal outputs. But lurking inside nearly every instruction tuning recipe is a crucial detail that has been overlooked:

The conventional loss is computed only on the response tokens!

But WHY?? 🙂

A couple of recent works have already started questioning it:

- Shi et al., 2025 (

) treat instruction tuning as a form of continual pretraining, applying loss uniformly over both prompt and response tokens. However, they only find it beneficial when lengthy prompts are coupled with brief responses or when only a small number of training examples are involved. - Huerta-Enochian and Ko (2024) (

) proposed using a small non-zero prompt loss weight (PLW) — it was found to be beneficial when working with instruction-tuning data containing short completions and that it can safely be ignored when working with instruction-tuning data containing longer completions. However, its applicability across diverse training and evaluation datasets remains unexplored. Moreover, the extent to which prompt token weights should depend solely on the relative length of completions to prompts remains unclear.

Meanwhile, several recent works (

So, this begs the question:

What if we assign different weights to prompt and response tokens during training? To control how much to tune on the prompt and response tokens?

This is exactly what WIT does — it lets you assign different weights to prompt and response tokens during training. And it turns out that this simple tweak goes a long way in improving the generalizability of the model!

Weighted Instruction Tuning (WIT)

Let \(\mathcal{D} = \{(\boldsymbol{P}_i, \boldsymbol{R}_i)\}_{i=1}^{N_{\mathcal{T}}}\) be an instruction tuning dataset with \(N_{\mathcal{T}}\) (prompt, response) pairs. Each prompt \(\boldsymbol{P}_i\) includes an instruction (implicit or explicit) and optionally some input, while \(\boldsymbol{R}_i\) is the expected ground-truth response.

If \(\lvert\boldsymbol{S}\rvert\) denotes the number of tokens in a sequence \(\boldsymbol{S}\), then:

\[\boldsymbol{P}_i = \left\{p_i^{(1)}, p_i^{(2)}, \ldots, p_i^{(\lvert\boldsymbol{P}_i\rvert)}\right\}\] \[\boldsymbol{R}_i = \left\{r_i^{(1)}, r_i^{(2)}, \ldots, r_i^{(\lvert\boldsymbol{R}_i\rvert)}\right\}\]The WIT loss is given by:

\[\mathcal{L}_{WIT} = -\frac{\sum\limits_{i=1}^{N_{\mathcal{T}}}\left[\lambda_p \cdot \sum\limits_{j=1}^{\lvert\boldsymbol{P}_i\rvert} \log \mathbb{P}_{\mathcal{M}}\left(p_i^{(j)} |\; p_i^{(1)},\ldots, p_i^{(j-1)} \right) + \lambda_r \cdot \sum\limits_{j=1}^{\lvert\boldsymbol{R}_i\rvert} \log \mathbb{P}_{\mathcal{M}}\left(r_i^{(j)} |\; r_i^{(1)},\ldots, r_i^{(j-1)} \right)\right]}{\sum\limits_{i=1}^{N_{\mathcal{T}}}\Big(\mathbb{I}{(\lambda_p \neq 0)}\cdot\lvert \boldsymbol{P}_i\rvert + \mathbb{I}{(\lambda_r \neq 0)}\cdot \lvert\boldsymbol{R}_i\rvert\Big)}\]where \(\mathbb{I}(\cdot)\) is the indicator function, \(\lambda_p\) is the prompt token weight, and \(\lambda_r\) is the response token weight. \(\mathcal{L}_{WIT}\) computes the weighted sum of log-probabilities – scaling the log-probabilities of prompt tokens by \(\lambda_p\) and those of response tokens by \(\lambda_r\) – and then normalizes by the count of tokens with non-zero weight. The indicator function (\(\mathbb{I}\)) ensures that the weighted sum is divided exactly by those tokens whose weight is non-zero. Note that the conventional instruction tuning loss \(\mathcal{L}_{IT}\) is a special case of \(\mathcal{L}_{WIT}\) for \((\lambda_p, \lambda_r) = (0,1)\) and continual pre-training is a special case of \(\mathcal{L}_{WIT}\) for \((\lambda_p, \lambda_r) = (1,1)\).

So…Does it work?

YES!! And that too consistently, across settings:

We ran an extensive set of experiments to test WIT across a wide range of settings. Here’s what we varied:

- 5 Language Models: LLaMA-3 (1B, 3B, 8B), Gemma-2B, and Mistral-7B

- 3 Instruction Tuning Datasets: LIMA (1K high-quality prompts), Alpaca-Cleaned (52K), and Tülu-v2 (150K diverse examples)

- 5 Diverse Evaluation Benchmarks: spanning knowledge (MMLU), reasoning (BBH), instruction following (IFEval), and conversation (AlpacaEval, MT-Bench)

Across the board, WIT outperforms the conventional instruction tuning loss

- On average, WIT achieves a relative gain of 6.55% over the standard loss.

- In some cases, the relative gains are huge — for example, +20.25% for Mistral-7B on Alpaca-Cleaned!

- Even better: these models serve as a stronger base for subsequent preference alignment tuning (e.g., DPO)! — for more details, please refer to our paper!

Key Observations:

- Low-to-Moderate Prompt-Token Weight Yields Best Performing Models. In ~81% of (model, training data, evaluation benchmark) combinations (61 out of 75), the best results were achieved when prompt tokens had low-to-moderate (0-0.6) weights. Furthermore, in 56% of the combinations, (43 out of 75), the optimal prompt-token weight is non-zero, strongly suggesting that ignoring prompt tokens for instruction tuning is suboptimal.

- Moderate-to-High Response-Token Weight Yields Optimal Models. \(\lambda_r = 1\) (i.e., full weight on response tokens) was optimal in only 24% of the (model, training data, evaluation benchmark) combinations (18 out of 75). Furthermore, in ~73.33% of the combinations, (55 out of 75), a moderate-to-high (0.4-1) response-token weight, yielded the best performance.

- Varying Effects of Response-Token Weight on Instruction Adherence and Conversational Fluency. For IFEval, which measures instruction-following ability, lower response weights are favoured – in 60% of (model, training data) combinations (9 out of 15), \(\lambda_r ≤ 0.4\) is optimal. In contrast, conversational fluency benchmarks – AlpacaEval and MT-Bench –– prefer relatively higher response weights –– in 60% of combinations, (18 out of 30), \(\lambda_r ≥ 0.6\) is optimal, and in 80% cases, \(\lambda_r ≥ 0.4\) yields best performance.

- Prompt-Only Tuning Also Enhances Base Model Capabilities. Even when no loss is applied on response tokens, i.e., tuning exclusively on prompts can also improve instruction adherence — especially with large/diverse datasets (like Tülu-v2).

🔮 Some Hints for Future Research

Building on the empirical results, we looked at broader patterns and preliminary insights that could inspire future studies on the interplay between task characteristics and token weighting:

Key Trends:

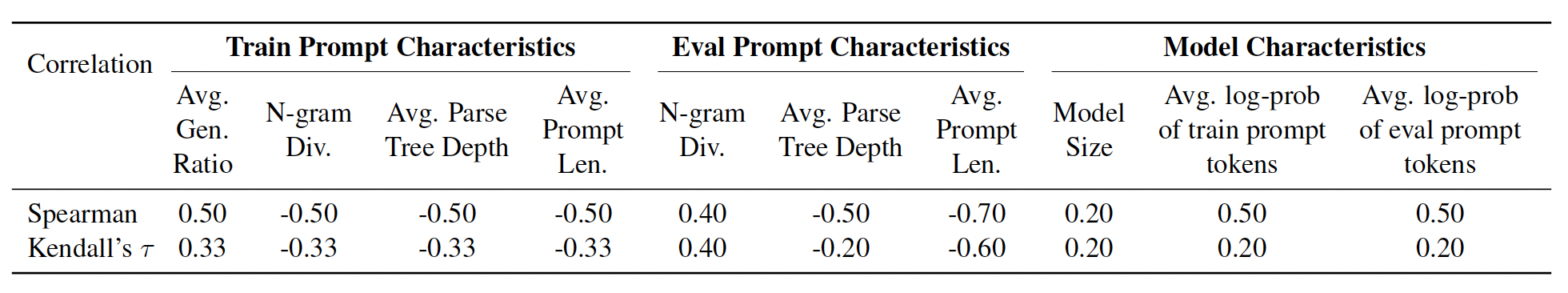

- Role of finetuning data While the average optimal prompt-token weight for all finetuning datasets is in the low-to-moderate range, it is comparatively lower for Tülu-v2 compared to Alpaca-Cleaned or LIMA. To better understand the possible dataset characteristics contributing to these trends, we study the prompt characteristics in the finetuning datasets, such as the average prompt length and the average generation ratio (i.e., the ratio of response length and prompt length) to capture the length characteristics, n-gram diversity of prompts to capture lexical diversity, and the average depth of prompts’ dependency parse tree to capture syntactic complexity. We find that the average generation ratio is positively correlated with the optimal prompttoken weight, while the average prompt length exhibits a negative correlation. This indicates that higher prompt-token weights tend to be preferred when the finetuning data contains longer completions relative to prompts, but not necessarily when the prompts themselves are longer. Furthermore, both lexical diversity, as measured by n-gram diversity, and syntactic complexity of the prompts are observed to negatively influence the optimal prompt-token weight.

- Role of evaluation benchmarks We observe that the optimal prompt-token weight varies from low to moderate, ranging from 0.17 for BBH to 0.48 for IFEval. As with finetuning data, a lower prompt-token weight yields better performance on benchmarks with longer prompts; syntactic complexity of the prompts also has a negative correlation with optimal prompttoken weight. However, unlike with training data, we observe that the lexical diversity of evaluation benchmarks is positively correlated with the optimal prompt-token weight.

- Role of Language Models We observe that the optimal prompt-token weight varies from low to moderate, ranging from 0.20 for Llama-3-3B to 0.42 for Gemma-2-2B. To better understand the potential factors contributing to these variations, we obtain model-dependent characteristics of train datasets and evaluation benchmarks, such as the average next-token log probabilities of prompts from finetuning datasets and evaluation benchmarks. The average next-token log probability is observed to be positively correlated with prompt-token weight suggesting that if a model has higher perplexity on prompts of a certain dataset, then a lower prompt-token weight can be more suitable. Furthermore, model size has a weak positive correlation with optimal λp.

Conclusion and Future Directions

- The Instruction Tuning Loss is indeed a dial that is worth tuning!

- Weighted Instruction Tuning (WIT) that assigns low-to-moderate weight to prompt tokens and moderate-to-high weight to response tokens, is a simple yet effective alternative to the conventional instruction tuning loss — it also serves as a stronger base for subsequent preference alignment tuning (e.g., DPO)!

- Future work could explore more adaptive ways to assign weights to individual tokens — e.g., based on token informativeness or model perplexity etc!